Tanisha Singh is getting ready for work early one morning and cooking a simple curry for her lunchbox when she realizes she's out of tomatoes. Onions are already frying in the pan. Going out to buy vegetables is not an option, as local vegetable vendors won't be open. So Tanisha picks up her phone. On a quick-delivery app, tomatoes are available. Eight minutes later, the doorbell rings. The tomatoes have arrived. What might feel remarkable in some parts of the world has become commonplace in Delhi and other big Indian cities. Groceries, books, soft drinks, and even the occasional iPhone can now be delivered to people's doorsteps in minutes, making convenience a quick habit that many can't live without.

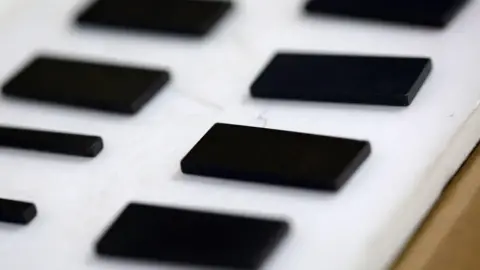

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets but operate from 'dark stores' strategically located close to urban homes. These facilities enable delivery riders to reach customers quickly, turning immediate access to goods into a daily reality.

However, this rapid pace of delivery also highlights the struggles of gig economy workers who often manage demanding schedules with limited rights, facing low earnings while balancing high expectations from delivery apps. Delivery driver Muhammad Faiyaz Alam exemplifies this narrative, as he navigates the urban landscape to complete multiple deliveries daily. Compensated only through commissions, risks such as stolen phones or traffic violations further complicate their precarious positions.

As urban life in India shifts toward an expectation for instant consumerism, the increasing reliance on quick deliveries poses questions about sustainability, labor rights, and the evolving structure of the gig economy amidst the backdrop of everyday life.

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets but operate from 'dark stores' strategically located close to urban homes. These facilities enable delivery riders to reach customers quickly, turning immediate access to goods into a daily reality.

However, this rapid pace of delivery also highlights the struggles of gig economy workers who often manage demanding schedules with limited rights, facing low earnings while balancing high expectations from delivery apps. Delivery driver Muhammad Faiyaz Alam exemplifies this narrative, as he navigates the urban landscape to complete multiple deliveries daily. Compensated only through commissions, risks such as stolen phones or traffic violations further complicate their precarious positions.

As urban life in India shifts toward an expectation for instant consumerism, the increasing reliance on quick deliveries poses questions about sustainability, labor rights, and the evolving structure of the gig economy amidst the backdrop of everyday life.